Good advice.

I was recently reminded of some good advice that I wish to share with you.

- Be a patient listener.

- Never be untidy.

- Never look bored.

That’s good advice. Perhaps from a Father telling his daughter how to act appropriately in a public setting.

- Wait long enough for the other person to reveal their religious views or political opinions then choose the same ones.

- Never pry into a person’s personal circumstances (they’ll tell you all eventually).

- Never get drunk before or during a business meeting.

More good advice, perhaps from a boss training a new employee on how to get the best deal out of a potential client.

- Never discuss illness, unless some special concern is shown.

- Never boast – just let your importance be quietly obvious.

Great advice about the importance of being polite. Maybe given by a college professor to his students.

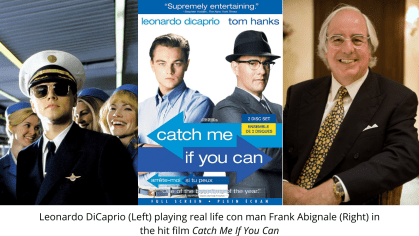

All of the statements of advice were taken from the journal of a professional… a professional con-man!

“It is being a patient listener, not fast-talking, that gets a con-man his coups.” – Victor Lustig

Enter Victor Lustig.

Victor Lustig was born in 1890. Born in Bohemia, Victor was the best, most  notorious conman of the early 20th century. Victor had big plans; he committed to his studies in school, became fluent in a number of European languages and English – then set out to ply his trade. A life of crime.

notorious conman of the early 20th century. Victor had big plans; he committed to his studies in school, became fluent in a number of European languages and English – then set out to ply his trade. A life of crime.

Victor Lusting wasn’t interested in carrying a gun, a knife, or threatening violence. He’d gotten into a scrum once during college, siding with a pretty girl that already had a boyfriend. That fiasco earned him a reputation as a lady’s man and a large scar from a knife on his face. He knew then that he had no stomach for violence.

He wasn’t interested in climbing drainpipes and burgling goods from honest folks. Victor had set his lofty sights on being the best “confidence man” he could be. A professional. An artist. A con artist.

Before World War I Victor plied his trade on unsuspecting fellow travelers aboard ocean liners headed from the ports of France to New York in the United States. For the price of a first-class ticket (about $150.00), Lustig had 5 or 6 days to ingratiate himself to the passengers, he’d then wow them with tales of his Broadway smash productions. He dressed like he had money. His polyglot skills and obvious high level of education made it easy for the other passengers to assume he came from wealth.

What really hooked them was greed.

When Lustig finally got to the point of currying money from them, an investment in his next hit show, he didn’t have to twist any arms. The high rollers were more than willing to shell out their cash as an investment in Victor Lustig’s next Broadway hit.

Remember, you could make a lot of money on a hit play in Victor Lustig’s day. Charles H. Hoyt’s A Trip to Chinatown started on Broadway in 1891 and ran for a record of 657 performances.

The men who ran the ocean liners were just as greedy. The average steerage ticket was about $30.00. It only took about 60 cents a day for 5 or 6 days to feed and house someone in steerage. That meant for the $30 investment, the trip only cost the ocean liner’s owner about $3.60 per passenger in this lowest class of ship travel. On steerage alone, the owners would make 50-60 thousand dollars in profit.

The men who ran the ocean liners were just as greedy. The average steerage ticket was about $30.00. It only took about 60 cents a day for 5 or 6 days to feed and house someone in steerage. That meant for the $30 investment, the trip only cost the ocean liner’s owner about $3.60 per passenger in this lowest class of ship travel. On steerage alone, the owners would make 50-60 thousand dollars in profit.

Greed has at its roots the fallacy of independence and security that money will bring. The accumulation of personal wealth is arguably the primary motivation for many if not most people. Their primal motivation might still be procreation, but greed drove their desires to seek out more money and more possession than they had, which in turn drove the need for more money in a vicious circle. Too much greed can make us blind to cons and scams. Greed can make us stupid.

Victor turned his transatlantic scams into easy money. He’d work the folks from France to the US, then relax and play cards back to a French port, then start all over again.

His plan served him well until 1914 and the beginning of World War I. The war suspended passenger travel across the Atlantic. Victor had a good run but needed a new scam. You see even though his wealth grew immensely, so did his appetite for material goods and living ‘high on the hog’. His greed forced him to remain in the ‘scam game’.

Victor spent the next few years turning junk bonds into cash in New York. He had a couple of close calls with Broadway investors near Wall Street that thought they recognized him. He had no love of police officers and couldn’t afford to be recognized so he headed back to Paris, France in 1922.

He pulled enough ‘short scams’ to keep him in the life he was by now accustomed to, but he craved being back in the big time and his back accounts were by now dwindling to the lowest state since 1910.

Lines of Comm.

Line of communication are those routes that connect military units on the ground in one area with their supplies located in another area, generally outside the kinetic area of the battlespace. Having secure lines of comm, and an open line of communication, mean that a unit on the move in or through a kinetic combat area can operate effectively without fear of being cut off or ‘going black’ on ammo, water or supplies.

Lines of communication can also refer to the time it takes for communication to travel from one location to another. For example; it took 5 or 6 days to travel across the Atlantic. Probably another week before the rich passengers figured out, they had been duped by Victor Lustig.

Lustig switched ports and liners, so that meant it was another week before law enforcement could check the thousands of folks streaming into the United States in the next few weeks (matching aliases against physical descriptions) before they had a chance at catching Victor.

As it was, Victor’s transatlantic scam lasted almost 5 years and set him up with enough money to live comfortably for the rest of his life. But that wasn’t enough for Victor Lustig.

Being an intellectual, Victor sat down at his desk and pored over the newspapers to see if there was an angle he would exploit. He found it in the scrap metal industry.

The Scrap metal scam of the century.

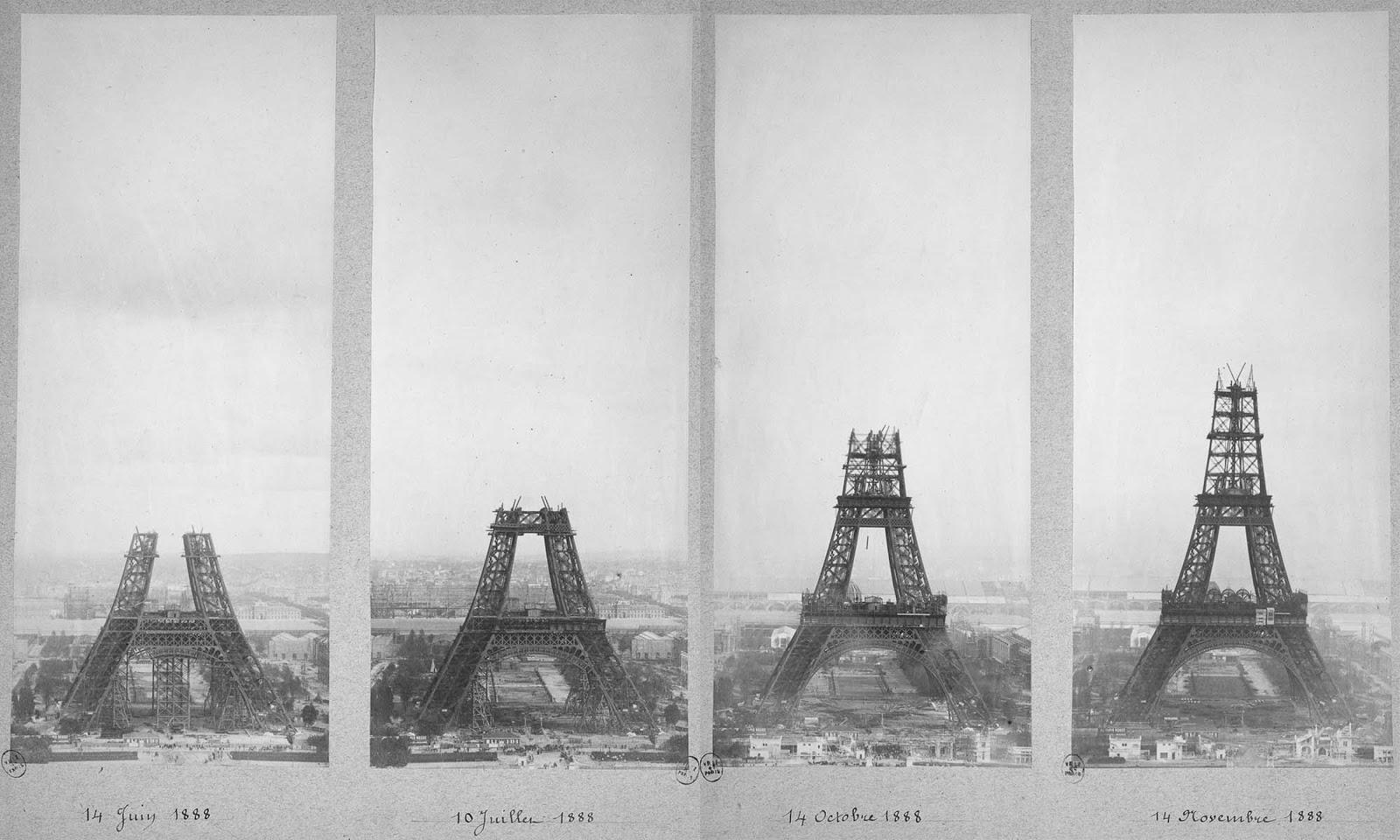

Victor found a number of articles and editorials about the Eiffel Tower. The 1,063-foot tower was built between 1887 and 1889 by Engineer Gustave Eiffel and his construction company and the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair.

1,063-foot tower was built between 1887 and 1889 by Engineer Gustave Eiffel and his construction company and the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair.

By 1925, the Eiffel tower which had always been controversial and arguably one of the most recognizable structures in the world was now 30 years old and showing its wear. Many of the iconic structures built for Olympic venues or World’s Fairs only last a few years after the event then are torn down or co-opted for another purpose.

Many of the articles stated that the ‘juice’ was no longer worth the squeeze and that the maintenance costs for the Eiffel Tower were now too much to bear. The tower had fallen in disrepair and needed both engineering work and a fresh coat of paint to restore it.

To protect the Eiffel Tower from corrosion it must be covered with a thick coat of paint renewed every 7 years. Gustave Eiffel created the repainting schedule and it is still used today. You see, the Eiffel Tower is made of iron, not steel. The special brand of ‘puddle iron’ comes from the Pompey forges in the East of France. That means it needs a little more love and care than other monuments.

Gustave Eiffel was also an important man, so having the tower in disrepair was unthinkable even though it was expensive. Eiffel’s Levallois Perret factory near Paris, France was also responsible for the structural framework of the Statue of Liberty which was erected in 1886 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the American Declaration of Independence.

Victor Lustig forged a number of documents then approached engineering firms and scrap metal companies around France, posing as an authorized agent of the government. His job? To find the highest bidder for the metal contained within the tower. The highest bidder would get to dismantle the Eiffel Tower and reclaim the precious puddle iron for other projects. A lucrative offer.

Victor Lustig forged a number of documents then approached engineering firms and scrap metal companies around France, posing as an authorized agent of the government. His job? To find the highest bidder for the metal contained within the tower. The highest bidder would get to dismantle the Eiffel Tower and reclaim the precious puddle iron for other projects. A lucrative offer.

Victor met with some folks in their offices, some he encountered on the street, with each he followed his own rules as listed in the first few sentences of this Lessons Learned. He invited all of them to a swanky hotel where he fed them an amazing meal, softened them with champagne, and laid out the process for bidding on the Eiffel Tower.

Victor Lustig was also a master of playing the margins. With most of the participants, it was a straight-up scam. You pay me money for a legitimate government bid and I will choose the appropriate winner and they will be the new owner of the bridge. But as Lustig learned more about his ‘marks’ he found one in particular that seemed the neediest.

He approached this man after all the other scrap metal bidders and engineers left the hotel. He had rightly suspected that this man wanted to win the bid badly enough to engage in a side deal. Victor told the man if he paid an additional $70,000.00 dollars that he (Victor) would ensure that this man’s bid would be the winner.

Victor took the money and drove to Austria where he remained in a 5-star hotel as he scoured the newspaper for any articles on his Eiffel Tower scam. He had speculated that those he duped would be too embarrassed to go to the police – and he had been right. None of the men, least of all the one that he had bilked the most money from – had gone to the authorities.

This meant only one thing to Lustig. Time to hit France with the Eiffel Tower scam again!

Lustig took a train back to France, forged more documents now with the title of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. He took to the streets and sought out engineers willing to tear down the Eiffel Tower – this time because the Tower didn’t fit in with the other monuments located around Paris. It was an ‘eyesore’ and had to go.

Lustig took a train back to France, forged more documents now with the title of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. He took to the streets and sought out engineers willing to tear down the Eiffel Tower – this time because the Tower didn’t fit in with the other monuments located around Paris. It was an ‘eyesore’ and had to go.

Again, Victor Lustig new enough from the information sources available to him to exploit that information and get inside the head of the people of Paris, France at the time. He found a small segment of those people that wanted the Eiffel Tower torn down, then he went after that small group with a vengeance. He sought them out, pretended that he was on their side, then he appealed to their greed.

Once again, Victor Lustig was in a fancy hotel in Paris surrounded by people who wanted to bid on buying the Eiffel Tower in order to tear it down and profit on the scrap. Lustig filled his pockets and his bank accounts, then fled for the US, fearing that the law would soon put an end to his Eiffel Tower scams.

Stateside Victor.

Lustig was living in style, traveling around the United States pulling short scams here and there just for fun. He had one trick that worked well in Europe, but to his knowledge hadn’t been tried in America.

He took what was a simple magician’s wooden box, one where you could put a dollar in one side and after winding the cranks along the side, a ten dollar bill would emerge from the other side. It was a simple scam really, requiring only a little engineering and a lot of acting. Whatever ‘bill’ went in the left side was pushed into the bottom of the box. While the cranks were turned, whichever ‘bill’ had been put into the top of the box would emerge slowly from the slot on the other side.

It didn’t matter what you put in, just the sequence. For example, you could put pieces of blank paper the size of a one-dollar bill into the left side of the machine. If you kept putting them in and cranking, sooner or later the same number of one-dollar bills would come out of the right side of the machine. It was all pre-planned and both a hoax and a scam. It did however MAKE MONEY literally and (with enough acting and distraction from the seller) in front of one’s eyes, intriguing the potential buyer.

Lustig wasn’t “two-bit”, he was big time. Victor Lustig wanted big bucks on every scam, so he set up his magic boxes so that when a dollar bill entered the left side, a one hundred dollar bill came out of the right side. No matter how many times his ‘mark’ would try it, he would make a hundred for every dollar he spent.

Lustig would lose a few hundred dollars while demonstrating the box, which he would then turn around and sell for a couple of thousand dollars, making himself an amazing profit each time. Lustig also knew that all he would have to do is keep ahead of the news, keep on the move, and he wouldn’t get caught. Few of the people he scammed went to the police after discovering how stupid they were to get scammed in this manner.

Victor was once caught at a Chicago train station by a Texas Sheriff who had bought one of his boxes and when it stopped working felt scammed. The Sheriff had tracked Victor down across the country and was now committed to bringing Victor Lustig to justice. Lustig was so smooth that he convinced the Texas Sheriff that he had been using the money box “all wrong”. Lustig reset the box with fresh money, showed the Sheriff the hundred dollar bills coming from the machine, and that was enough to convince the Sheriff who walked off turning the cranks as Victor ran for it, barely escaping by train.

After that, Victor did a few high stakes counterfeiting scams that paid well and one more noteworthy or memorable scam just for fun, this time pulling a fraud on Al Capone.

Lustig convinced Al Capone that he had a new scam and needed $50,000.00 stake money. Capone gave it over. Lustig put the $50,000.00 in an interest-bearing account and waited a few months. He then took the $50,000.00 back to Capone and said that he was sorry, but the plan had fallen through. He and Capone parted ways, Al Capone thinking that Victor Lustig was a ‘stand up’ guy that he could trust. A few months later, Lustig went back to Capone to borrow $5000.00. This was only 10 percent of the amount that Victor had returned to Capone, so Capone quickly said ‘yes’ to the loan. That was the last Al Capone saw of Victor Lustig or that 5 grand.

Victor Lustig kept passing counterfeit money and pulling the bank loan  scam until his luck ran out – even though he no longer needed the money. Most likely it was due to the psychological lure of greed combined with the electrochemical neurotransmitters associated with the thrill. Victor was caught, convicted of multiple frauds, and sentenced to a dozen years in jail. He attempted an escape, and that got him sent to ‘The Rock’, Alcatraz where he would die of pneumonia, penniless and alone in 1947.

scam until his luck ran out – even though he no longer needed the money. Most likely it was due to the psychological lure of greed combined with the electrochemical neurotransmitters associated with the thrill. Victor was caught, convicted of multiple frauds, and sentenced to a dozen years in jail. He attempted an escape, and that got him sent to ‘The Rock’, Alcatraz where he would die of pneumonia, penniless and alone in 1947.

So What?

Greed works both ways. It takes a Scam Artist (an ‘artist’, nonetheless) and a ‘mark’. A mark, sucker, stooge, rube, or ‘Gull’ (from gullible) are all words associated with a mark – the victim of a con (scam, hustle, or grift).

Victor Lustig was successful because he studied people. He studied them with the intent of defrauding them. He also engaged in Urban Masking and Social Camouflage, perfecting his work with The Gift of Time and Distance until he had his act down perfectly. His final step was to use psychology to determine who was weak enough to scam – yet who was also likely too proud to want to be embarrassed by going to the cops. Victor Lustig created the perfect storm of fraud – until he too got greedy – and lost his Situational Awareness long enough to get caught.

Victor died in jail.

If you lose your SA and because a pawn in a scheme, you could die on the street or in your home, the victim of a criminal not averse to violence. The key is creating a baseline then measuring the situation you are up against for likelihood. If the artifacts and evidence add up to being “too good to be true”, they likely are – and you need to walk or run away. Training can change your perspective.

Training changes behavior.

- Greg

Comments are closed